There has been debates related to online and blended learning from a perspective of learner experiences in terms of student satisfaction, engagement and performances. In this paper, we analyze student feedback and report the findings of a study of the relationships between student satisfaction and their engagement in an online course with their overall performances. The module was offered online to 844 university students in the first year across different disciplines, namely Engineering, Science, Humanities, Management and Agriculture. It was assessed mainly through continuous assessments and was designed using a learning-by-doing pedagogical approach. The focus was on the acquisition of new skills and competencies, and their application in authentic mini projects throughout the module. Student feedback was coded and analyzed for 665 students both from a quantitative and qualitative perspective. The association between satisfaction and engagement was significant and positively correlated. Furthermore, there was a weak but positive significant correlation between satisfaction and engagement with their overall performances. Students were generally satisfied with the learning design philosophy, irrespective of their performance levels. Students, however, reported issues related to lack of tutor support and experiencing technical difficulties across groups. The findings raise implications for institutional e-learning policy making to improve student experiences. The factors that are important relate to the object of such policies, learning design models, student support and counseling, and learning analytics.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The world is going through tough times with the Covid-19 pandemic. Inevitably, there has been severe impacts on education systems around the globe. Schools and universities were closed, and millions of kids, adolescents and young adults have been out of schools and universities. Nichols (2003) pointed out that the Internet could be seen as (i) another delivery medium, (ii) as a medium to add value to the existing educational transaction or, (iii) as a way to transform the teaching and learning process. The research and discourse surrounding quality of online learning provisions, student engagement and satisfaction has been ongoing by both proponents and opponents of online learning (Biner et al. 1994; Rienties et al. 2018). With the abrupt shift and uptake of online learning, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, such discourse finds its relevance much beyond the classic academic research and debate. It is linked to the future of teaching and learning in technology-enabled learning environments. Arguably, the adoption of technology has disrupted the traditional teaching practices as teachers often find it difficult to adjust and connect their existing pedagogy with technology (Sulisworo 2013). Similarly, if informed policy decisions are not taken, this can affect the knowledge transfer processes as well as reduce the efficiency of teaching and learning processes (Ezugwu et al. 2016).

One of the challenges of online learning relates to students’ learning experiences and achievement. Sampson et al. (2010) stated that students’ satisfaction and outcomes are good indicators for assessing the quality and effectiveness of online programs. It is of concern for institutions to know whether its students, in general, are satisfied with their learning experience (Kember and Ginns 2012). Another essential element for quality online education is learner engagement. Learner engagement refers to the effort the learner makes to promote his or her psychological commitment to stay engaged in the learning process, to acquire knowledge and build his or her critical thinking (Dixson 2015). While there are different conceptualisations of student engagement (Zepke and Leach 2010), advocates of learning analytics tend to lay emphasis on the analysis of platform access logs including clicks on learning resources when it comes to student engagement in online learning (Rienties et al. 2018). The proposition is that being active online through logins, active sessions and clicks actually reflects actual engagement in an online course and result in better student performances. However, this model mainly works in classic online modules, and there is limited availability of literature measuring students’ engagement in activity-based hybrid learning environments where there is a mix online and offline activities (Rajabalee et al. 2020).

In this research, the aim was to investigate the relationships between students’ reported engagement, their satisfaction levels and their overall performances in an online module that was offered to first-year University students of different disciplines (Science, Engineering, Agriculture, Humanities, Management). The learning design followed an activity-based learning approach, where there was a total of nine learning activities to complete over two semesters. The focus was on skills development and competency-based learning via a learning-by-doing approach. There were 844 students enrolled on the module, and they were supported by a group of seven tutors. The end of module feedback, comprising mainly of open-ended questions, aligned with the Online Student Engagement (OSE) model, and the Online Learning Consortium model of student satisfaction were coded and analysed accordingly. Furthermore, the correlation between student satisfaction, engagement and their performances were established.

The findings of this research contribute to the existing knowledge through new insights into determining students’ engagement in online courses that follow an activity-based learning design approach. It is observed in this study, in line with other research that learning dispositions, such as the reported engagement, perceived satisfaction and student feedback elements could be useful dimensions to add to a learning design ecosystem to improve student learning experiences with the objective to move towards a competency and outcomes-based learning model. Based on the results and findings, the implications for institutional e-learning policy are discussed.

Learner satisfaction and experiences are crucial elements that contribute to the quality and acceptance of e-learning in higher education institutions (Sampson et al. 2010). Dziuban et al. (2015) reported that the Online Learning Consortium (formerly known as Sloan Consortium) considered student satisfaction of online learning in higher education as an essential element to measure the quality of online courses. Different factors influence learner satisfaction such as their digital literacy levels, their social and professional engagements, the learner support system including appropriate academic guidance and the course learning design (Allen et al. 2002).

According to Moore (2009), factors such as the use of learning strategies, learning difficulties, peer-tutor support, ability to apply knowledge and achievement of learning outcomes indicate those elements that impact on the overall satisfaction of students in online learning. A learning strategy is a set of tasks through which learners plan and organize their engagement in a way to facilitate knowledge acquisition and understanding (Ismail 2018). Enhancing the learning process with appropriate learning strategies may contribute to better outcomes and performances (Thanh and Viet 2016). Aung and Ye (2016) reported that students’ success and achievement were positively related to student satisfaction.

Students, in online courses, often experience learning difficulties, which encompass a range of factors such as digital literacy, conceptual understanding, technical issues and ease of access (Gillett-Swan 2017). These difficulties if not overcome on time, tend to reduce learning effectiveness and motivation, and may also affect their overall satisfaction (Ni 2013). Learner support may include instructional or technical support, where tutors and other student peers engage collectively to help students tackle issues that they encounter during the course. Such support, especially when students face technical difficulties is vital to overcome challenges and impacts on overall student satisfaction (Markova et al. 2017). The ability of students to apply knowledge, and to achieve the intended learning outcomes, also impacted on student satisfaction and quality of learning experience (Mihanović et al. 2016).

Student perception is the way students perceive and look at a situation from a personal perspective and experience. When students have a positive perception, they are more likely to feel satisfied with the course (Lee 2010). It is, therefore, crucial to understand how students think about a course, certainly to determine its implications on their academic experiences. A negative feeling is an emotion that students sometimes express concerning their learning experience. It could be in the form of anxiety, uneasiness, demotivation and apprehension or in terms of their readiness to use technology (Yunus et al. 2016). At the same time, negative feeling tends to have an impact on student online learning experience and their satisfaction (Abdous 2019). Learner autonomy relates to students’ independence in learning. It indicates how students take their responsibility and initiative for self-directed learning and organize their schedules. Cho and Heron (2015) argued that learner autonomy in online courses influences student experiences and satisfaction.

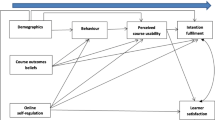

Student satisfaction is an essential indicator of students’ overall academic experiences and achievement (Virtanen et al. 2017). There are different instruments to measure student satisfaction in an online environment. Using survey questionnaires is generally standard practice for measuring learner satisfaction. Over the years, a variety of tools such as Course Experience Questionnaire (Ramsden 1991), National Student Survey (Ashby et al. 2011) and Students’ Evaluations of Educational Quality (Marsh 1982), were developed and used to measure student satisfaction. The Satisfaction of Online Learning (SOL) is an instrument that was established to measure student’s satisfaction in online mathematics courses (Davis 2017). It consisted of eight specific components, comprising of effectiveness and timeliness of the feedback, use of discussion boards in the classroom, dialogue between instructors and students, perception of online experiences, instructor characteristics, the feeling of a learning community and computer-mediated communication. The Research Initiative for Teaching Effectiveness (RITE) developed an instrument that focussed on the dynamics of student satisfaction with online learning (Dziuban et al. 2015). RITE assessed two main components namely, learning engagement and interaction value and, encompasses items such as student satisfaction, success, retention, reactive behaviour patterns, demographic profiles and strategies for success. Zerihun et al. (2012), further argued that most assessments of student satisfaction are based on teacher performance rather than on how student learning occurred. Li et al. (2016) used the Student Experience on a Module (SEaM) questionnaire, where questions were categorized under three themes, to explore the construct of student satisfaction. The three themes contain inquiries related to the (1) overall module, (2) teaching, learning and assessment and (3) tutor feedback.

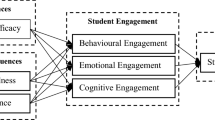

One of the critical elements affecting the quality of online education is the need to ensure that learners are effectively and adequately engaged in the educational process (Robinson and Hullinger 2008; Sinclair et al. 2017). Learner engagement refers to the effort the learner makes to promote his or her psychological commitment to stay engaged in the learning process to acquire knowledge and build his or her critical thinking (Dixson 2015). It is also associated with the learner’s feeling of personal motivation in the course, to interact with the course contents, tutors and peers, respectively (Czerkawski and Lyman 2016). There are different models to measure learner engagement in learning contexts. Lauría et al. (2012) supported the fact that the number of submitted assignments, posts in forums, and completion of online quizzes can quantify learner’s regularity in MOOCs. Studies using descriptive statistics reported that consistency and persistence in learning activities are related to learner engagement and successful performance (Greller et al. 2017). Learner engagement is also about exploring those activities that require online or platform presence (Anderson et al. 2014). Those online activities can be in the form of participation in discussion forums, wikis, blogs, collaborative assignments, online quizzes which require a level of involvement from the learner. Lee et al. (2019) reported that indicators of student engagement, such as psychological motivation, peer collaboration, cognitive problem solving, interaction with tutors and peers, can help to improve student engagement and ultimately assist tutors in effective curriculum design.

Kuh (2003) developed the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) benchmarks to evaluate students’ engagement through their skills, emotion, interaction and performance, applicable mainly to the traditional classroom settings. Another model relevant to the classroom environment is the Classroom Survey of Student Engagement (CLASSE) developed by Smallwood (2006). The Student Course Engagement Questionnaire (SCEQ) proposed by Handelsman et al. (2005), uses the psychometric procedure to obtain information from the students’ perspective to quantify students’ engagement in an individual course.

Roblyer and Wiencke’s (2004) proposed the Rubric for Assessing Interactive Qualities of Distance Courses (RAIQDC) which was designed as an instructive tool, to determine the degree of tutor-learner interactivity in a distance learning environment. Dixson (2010) developed the Online Student Engagement (OSE) scale model using the SCEQ model of Handelsman et al. (2005) as the base model. It aimed at measuring students’ engagement through their learning experiences, skills, participation, performance, and emotion in an online context. Dixson (2015) validated the OSE using the concept of behavioural engagement comprising of what was earlier described as observational and application learning behaviours. Dixson (2015) reported a significant correlation between application learning behaviours and OSE scale and a non-significant association between observation learning behaviours and OSE. Kahu (2013) critically examined student engagement models from different perspectives, namely behavioral, psychological, socio-cultural and holistic perspective. While the framework proposed is promising for a holistic approach to student engagement in a broader context of schooling, the OSE model as proposed by Dixson (2015) aligns quite well with the conceptual arguments of Kahu (2013) in the context of students’ engagement in online courses.

Gelan et al. (2018) measure online engagement by the number of times students log in the VLE to follow a learning session. They also found that students who tend to show higher regularity level in their online interaction and by attending more learning session were successful, compared to non-successful students. Ma et al. (2015) used learning analytics to track data related to teaching and learning activities to build an interaction-activity model to demonstrate how the instructor’s role has an impact on students’ engagement activities. An analysis of student emotions through their participation in forums and their performance in online courses can serve as the basis to model student engagement (Kagklis et al. 2015). They further observed that the students’ participation in forums was not directly associated with their performances. The reason was that most students preferred to emphasize working on their coursework as they will be given access to their exam, upon completion of a cumulative number of assignments and obtaining their grades. Therefore, although students tend to slow down their participation, they were still considered engaged in the online course.

Activity-based learning is an approach where the learner plays an active role in his or her learning through participation, experimentation and exploration of different learning activities. It involves learning-by-doing, learning-by-questioning and learning-by-solving problems where the learners consolidate their acquired knowledge by applying their skills learnt in a relevant learning situation (Biswas et al. 2018). These activities can be in the form of concept mapping, written submission and brainstorming discussions (Fallon et al. 2013). The study of Fallon et al. (2013) used the NSSE (National Survey of Student Engagement) questionnaire to measure and report on students’ engagement in learning materials and activities. They found encouraging results whereby they could establish that students responded positively to the activity-based learning approach, and there has been an enhancement in students’ participation and engagement. In line with this, Kugamoorthy (2017) postulated that the activity-based learning approach has motivated and increased student participation in learning activities as well as improved self-learning practices and higher cognitive skills. Therefore, student participation in activity-based learning model encourages students to think critically and develop their practical skills when they learn actively and comprehensively by involving cognitive, affective and psychomotor domains.

Research has demonstrated that activities that encouraged online and social presence, enhance and build learner confidence and increase performance are critical factors in engagement (Anderson et al. 2014; Dixson 2015). Furthermore, Strang (2017) found that when students are encouraged to complete online activities such as self-assessment quizzes, this promotes their learning and engagement and hence result in higher grades. Tempelaar et al. (2017) postulated that factors such as cultural differences, learning styles, learning motivations and emotions might impact on learner performances. Smith et al. (2012) deduced that students’ pace of learning and engagement with learning materials are indicators of their performance and determinants of learning experience and satisfaction. Macfadyen and Dawson (2012) found that variables such as discussion forum posts and completed assignments, can be used as practical predictors of learner performance, and thus can be used to help in learners’ retention and in improving their learning experiences. Pardo et al. (2017) utilized self-reported and observed data to investigate they can predict academic performance and understand why some students tend to perform better. They used a blended learning module the collected data related to students’ motivational, affective and cognitive aspects while observed data was related to students’ engagement captured from activities and interactions on learning management system. They deduced that students adopting a positive self-regulated strategy participated more frequently in online events, which could explain why some students perform better than others.

The module that was selected for this study was a first-year online module offered to students of the first year across disciplines. The module used an activity-based learning design consisting of nine learning activities. There were no written exams, and the first eight learning activities counted as continuous assessment, and the ninth activity counting as an end of module assessment. The module focused on the learning-by-doing approach, through authentic assignments such as developing a website, use an authoring tool, engage in critical reflection through blogging and YouTube video posts, general forum discussions as well as drill and practice questions such as online MCQs. The learning design principle that guided the pedagogical approach was the knowledge acquisition, application and construction cycle through sharing & reflective practice (Rajabalee et al. 2020). Although the module was fully online, it is necessary to point out, that not all of the learning activities necessitated persistent online presence for completion. For instance, students could download specific instructions from the e-learning platform, carry out the learning activities on their laptops, and then upload the final product for marking. The students further completed an end-of-module feedback activity using an instrument designed by the learning designers. The questions in the feedback activity were mainly open-ended and were in line with the OSE questionnaire and the Sloan instrument to measure student satisfaction in online courses. The approach was not survey based, but mainly taking a more in-depth qualitative approach as proposed by Kahu (2013). In this study, the research questions are set as follows:

The approach was to engage in an exploratory research study. The aim was to retrieve and analyze the data collected and accessible for an online module through the application of descriptive learning analytics. Such data are related to student satisfaction, their reported engagement in the online module and their overall performances. This study was based on the actual population of students who enrolled on the module. Consequently, there was no sampling done. Enrolment was optional as the module was offered as a ‘General Education’ course to first year students. It was open to students in all disciplines. All the students come from the national education system of Mauritius having completed the Higher School Certificate. The age group of the students were between 19 and 21. The student feedback was an integral component of the module and counted as part of a learning activity. Students who followed this module had initially agreed that information related to their participation and contributions in the course be used for research purposes in an anonymous manner. All student records were completely anonymized prior to classification and analysis of data.

The students came from different disciplines, as highlighted in Table 1. All participants had the required digital literacy skills, and they have followed the Information Technology introductory course as well as the national IC3 (Internet and Core Computing Certification) course at Secondary Level. Seven tutors and students facilitated the module with student groups ranging from 100 to 130 per group. The role of the tutors was mainly to act as a facilitator for the learning process and to mark learning activities and to provide feedback to the students. The Table 1 below, contains appropriate information about the participants across disciplines and gender for the module. Table 2 provides the information about the 179 students who did not complete the student feedback activity of the module.

“…This module has taught me many things, especially in terms of time management and developing a pedagogical approach to my work. This is something I never really paid attention to before working on Educational Technologies assignments. For once I could put myself in my teachers and lecturers’ places and comprehend the different approaches they have to take when explaining a certain topic!”

(Student B2456, female, Agriculture discipline, High performer category in Cumulative Assessment, Final Assessment = 7, Cumulative Assessment = 7.375)

“…the module helps us in our personal development as well as introduces us to what is necessary in education if ever, we are interested in the teaching field…”

(Student ID A4709, female, Science discipline, High performer category in Final Assessment, Final Assessment = 7.5, Cumulative Assessment = 7.5625)

“…This module has given me great experience…learnt strategies before doing any journals like I have done the outlines first in order to avoid messing the ideas and go out of subject…”

(Student ID B8920, female, Humanities discipline, Low performer category in both Final and Cumulative Assessment, Final Assessment = 2.567, Cumulative Assessment = 4.0625)

“…Each weekend, I dedicated 4 hours to do the homework… I planned my work on Saturdays and carried it out on Sundays. I gained better planning and better time management skills…”

(Student A4901, female, Law & Management discipline, Average performer category in Cumulative Assessment, Final Assessment = 5, Cumulative Assessment = 6.125)

The students described techniques that helped them to learn and achieve the outcomes. As can be seen, by the above comment, a feeling of fun was apparent given that students had to learn in different ways such as inquiry-based learning which gave them a degree of flexibility and variety of learning processes. E.g. there were consequential learning outcomes, which resulted in a particular competency about dealing with, different image formats. Furthermore, as could be seen in many comments, students understood the concept of “just-in-time” learning where they could acquire specific skills through research on Google. They could even view tutorials on YouTube at the time of execution of a particular task related to an assignment (e.g. conversion to ZIP format before uploading an assignment on the platform).

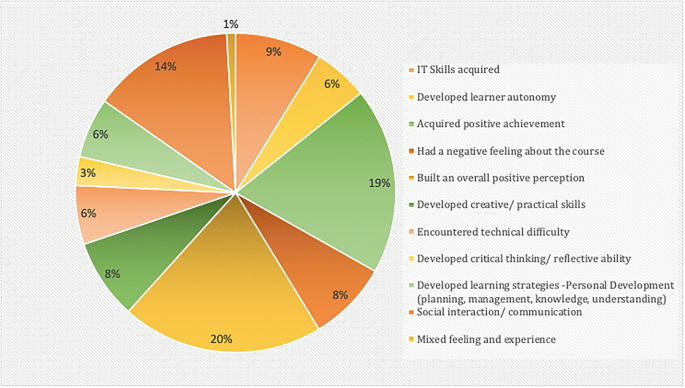

8.1% of the codes, however, mentioned some form of negative feeling and inadequate learning experience overall. These were mainly related to students not finding the pertinence of the module, lack of digital skills, or who had communication issues with peers and tutors. At the same time, another 6% of the codes highlighted technical difficulty experienced by students due to poor Internet connection or difficulty in solving technical issues including installation and configuration of software or uploading of their assignments.

“…I did encounter several difficulties. I would not understand how to use a program or as for the eXe software, I could not save my works…at times I had to do the activities again and again. It was tiring…”

(Student B2180, male, Engineering discipline, High performer category in Cumulative Assessment, Final Assessment = 6, Cumulative Assessment = 7.8)

“…it is difficult for me to complete it alone, I am not used to the different tool on the computer, sections has been more complicated, difficult to go throughout the steps without a basic knowledge of how to use the different functions on the screen of the computer…”

(Student B5681, female, Humanities discipline, Average performer category in Cumulative Assessment, Final Assessment = 6.3, Cumulative Assessment = 6.375)

“… less teacher-student interaction, less student-student interaction, in all there is a lack of communication, there were lack of feedback from our tutors about the learning activities being done. No result of how we were working…”

(Student B2107, male, Engineering discipline, Average performer category in Final Assessment, Final Assessment = 6, Cumulative Assessment = 6.6875)

“…Trouble with assignment…It was a disaster…I did the activities 1 to 4, 9 and 13 and even the feedback I am not sure what I did wrong because this site holds record of only 2 of my uploads…I think it is lacking in the communication department. I think that the forum is not effective…”

(Student B3527, female, Humanities discipline, Low performer category in Cumulative Assessment, Final Assessment = 6, Cumulative Assessment = 4.9875)

The codes representing a negative feeling and the occurrence of technical difficulties can provide interesting insights into either a range of pre-emptive or just-in-time measures that can be taken by course developers, tutors and administrators to provide timely support to the learners during the course itself. This may significantly improve the learning experience and overall perception of learners as if they are detected early, they can prevent dropouts, frustrations and poor performances from occurring. However, the positive side concerning the current module is that the codes representing negative feelings and technical difficulties represent 14.1% only of the total number of codes generated. Many of those who expressed that they had technical difficulties also highlighted what they did to overcome them. It is important to mention however, that in this module, the experience of technical difficulties and developing the necessary skills to deal with, then are part of the core learning outcomes, as many educators precisely abandon technology or show reluctance to embrace technology-enabled teaching precisely because of their lack of confidence in their own digital skills. Finally, 0.9% of total codes were reported as ‘Mixed feeling and experience’ where the students had neither a positive nor a negative experience in the course.

“…even if instructions were given, I used to find some activities really difficult…Overall it was a fun as well as difficult experience…” (Student A1261, female, Humanities discipline, High performer category in Cumulative Assessment, Final Assessment = 6.5, Cumulative Assessment = 7.175)

“I had difficulty to meet the deadlines as I was more stressed by my first-year core modules. I was also not very familiar with a lot of the computer directed tasks… I am quite satisfied with the work…”

(Student A2967, female, Humanities discipline, High performer category in Final Assessment, Final Assessment = 7.5, Cumulative Assessment = 6.9375)

“At the beginning of the module, I find quite interesting. Then, it was very tough… The storyboard was very interesting, yet I found quite problems on drawing the storyboard but fortunately, after many difficulties I succeeded in doing it…”

(Student B6023, female, Law & Management discipline, Average performer category in Final Assessment, Final Assessment = 7, Cumulative Assessment = 7.225)

“So, the only thing I can finally say is that educational technology’s module is neither so difficult nor easy…” (Student B3016, female, Humanities discipline, Low performer category in Final Assessment, Final Assessment = 5, Cumulative Assessment = 7.95)

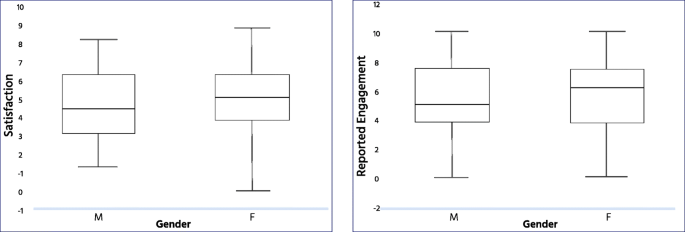

In summary, while there are some cases where students still complained about the lack of tutor responses and interactions while other students commended the independence they were given and found tutors’ support to be more than adequate. It further emerged that the majority of the students irrespective of overall performances reported a high level of satisfaction. The level of satisfaction was, therefore, not directly related to the performances as it could be observed that high performers could also express mitigated feelings. In contrast, some low performers reported a positive sense of satisfaction.

Student engagement is an important issue in higher education and has been the subject of interest from research, practitioner and policy-making perspectives. There are different models of engagement that have been studied and proposed. The reliability of self-reported data of students and the lack of a holistic model incorporating multiple dimensions have been the subject of critical analysis by researchers (Kahu 2013). The issue of engagement has also been widely discussed in the context of online learning and different instruments which are mainly survey-based such as the OSE model (Dixson 2015) have been developed. The challenge of a reliable model to define student engagement in online courses remains based on the findings of this research as well. In terms of practical course design, there is a need for learning designers to define beforehand, the student engagement model that would be applied prior to the start of a course, and then conceive their learning activities accordingly.

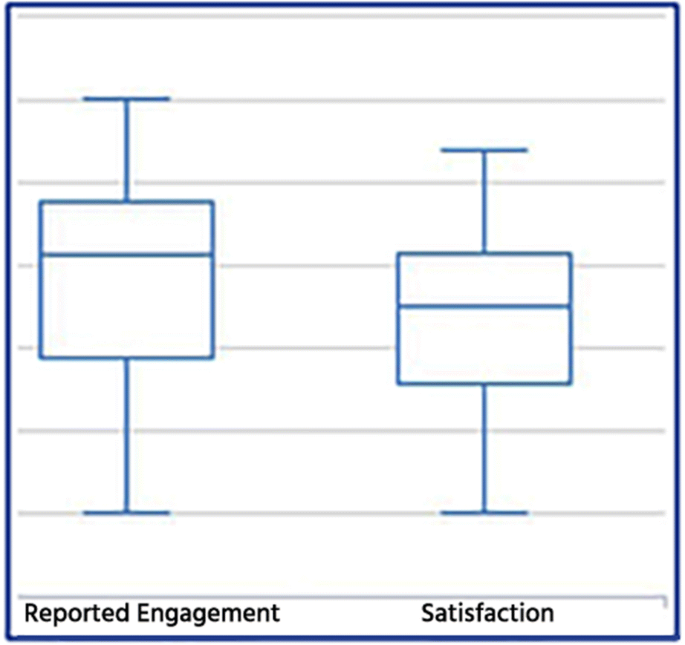

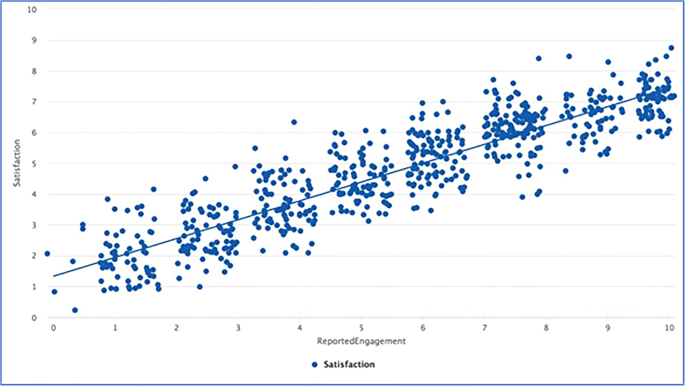

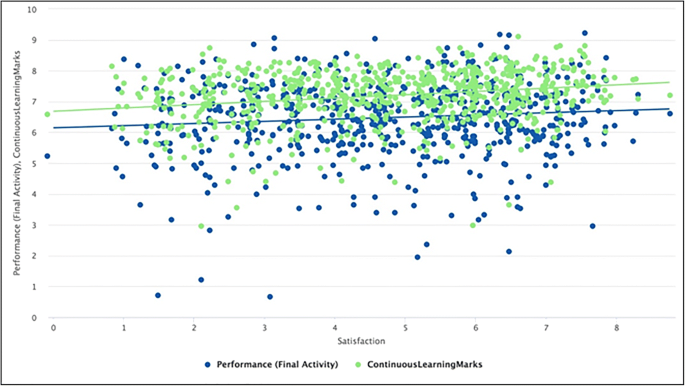

A positive, but weak association was established between reported engagement with respect to the continuous learning marks and the performances in the final activity. If reported engagement in this context can be defined as the extent to which the student felt connected and committed to the module, it does not necessarily imply that their performances (by way of marks achieved) would reflect that. The findings related to the association of the reported engagement of students concerning the different learning domains, however, contradict the findings of Dixson (2015) who reported a significant correlation between application learning behaviours and OSE scale and a non-significant correlation between observation learning behaviours and OSE. Regarding the reported satisfaction and engagement, it was observed that the higher level of reported engagement resulted in higher levels of satisfaction from the students. However, since the same feedback instrument was used to derive codes related to engagement and satisfaction, this might explain the relatively strong association between the two. This finding is however coherent with the claims of Hartman and Truman-Davis (2001) and Dziuban et al. (2015) who established that there is a significant correlation in the amount and quality of learner interaction with learner satisfaction.

It was also observed that tutor support had played an important part in shaping the students’ level of satisfaction as some students expressed negative feelings when the tutor support was not adequate. Proper academic guidance, as reported in the literature, is a contributing factor in learners’ performances, achievement and satisfaction (Earl-Novell 2006). While it has been established in the literature that in general student satisfaction is not linked to performances, a significant positive correlation was observed in this study between perceived satisfaction and both continuous learning marks and the final performance marks. However, the degree of association, as measured by the correlation coefficient (.108) was weak. In this respect, further analysis through linear regression revealed that perceived satisfaction was not a significant predictor of performances.

If the intention behind the adoption of e-learning is to improve the teaching and learning experiences of on-campus students as argued by Moore (2009) and Abdous (2019), institutional policies will need to focus mainly on digital learning and technology-enabled pedagogies. This is in line with the critical approach taken by Kahu (2013) arguing that student engagement should be about developing competencies in a holistic manner goes beyond the notion of just ‘getting qualifications’. In this research, the activity-based learning design was at the heart of the offer of such a course. The Internet acted mainly as a means to transform the teaching and learning process (Nichols 2003) as skills acquisition, and competency-based outcomes were critical to the learning design. The findings show that irrespective of the overall performances of the students, the majority of them appreciated the learning design, the educational experience, but not necessarily the fact that it was online. Therefore, such approaches mean that institutional leaders should reflect on how to design online courses using competency-based design to better engage students to improve student satisfaction and overall experiences. In that context, there is a need ensure that learning design guidelines is at the heart of the e-learning related policies. The core idea is to engage in a paradigm shift from teacher to learner-centred methods. Learner-centred approaches further imply that the right balance has to be established between mass-customization (one-size-fits-all), and personalized learner support within such environments. Learner support is an essential aspect of quality assurance to be taken into account in technology-enabled learning policies (Sinclair et al. 2017).

In this research, descriptive analytics was used to analyze data related to student performances, satisfaction and reported engagement. In line with Macfadyen and Dawson (2012), we can see a learning analytics approach has helped to give some constructive meaning to the data gathered on the e-Learning platforms to understand better our students’ learning patterns and experiences. Therefore, learning analytics is an essential disposition that institutional e-learning policies have to consider. Sentiment analysis, for instance can add value to the learner support framework, as it allows the tutor(s) to focus his or her efforts on supporting primarily those who are experiencing difficulties while maintaining a minimum level of interaction with those independent learners. This argument has been supported in the literature by different authors (Lehmann et al. 2014; Tempelaar et al. 2015).

The module under study relied mainly on asynchronous tutor intervention when it comes to learner support. Such a model of tutor support has been predominant in online distance education (Guri-Rosenblit 2009). However, with the exponential development in Internet infrastructure and video conferencing technologies, real-time synchronous tutor intervention is more and more being adopted, giving rise to the concept of “Distributed Virtual Learning (DVL)”. DVL allows for tutor-student interaction in real-time, especially where students report problems, or when built-in analytics such as sentiment analysis can flag students who are at risk. The concepts that embody DVL have to be duly taken into consideration by policymakers.

From this research, it emerged that students’ satisfaction and their engagement are essential elements defining their learning experiences. Analysis of the feedback revealed that technical difficulties and lack of tutor support create a sense of frustration even if the student ultimately performs well. It is important that such emotions are captured just-in-time during the time the module is offered as timely action can then be taken to address student concerns. At a time, where institutions are moving to e-learning to ensure continuity of educational services, there are important policy implications for the longer-term effectiveness in terms of learning outcomes and student experience.